Expressions

In Xtend everything is an expression and has a return type. Statements do not exist. That allows you to compose your code in interesting ways. For example, you can have a try catch expression on the right hand side of an assignment:

val data = try {

fileContentsToString('data.txt')

} catch (IOException e) {

'dummy data'

}

If fileContentsToString() throws an IOException, it is caught and the string 'dummy data' is assigned to the value data. Expressions can appear as initializers of fields, the body of constructors or methods and as values in annotations. A method body can either be a block expression or a template expression.

Literals

A literal denotes a fixed, unchangeable value. Literals for strings, numbers, booleans, null and Java types are supported as well as literals for unmodifiable collection types like lists, sets and maps or literals for arrays.

String Literals

A string literal is of type String. String literals are enclosed in a pair of single quotes or double quotes. Single quotes are more common because the signal-to-noise ration is better, but generally you should use the terminals which are least likely to occur in the string value. Special characters can be quoted with a backslash or defined using unicode notation. Contrary to Java, strings can span multiple lines.

'Hello World !'

"Hello World !"

'Hello "World" !'

"Hello \"World\" !"

"Hello

World !"

Character Literals

Character literals use the same notation as String literals. If a single character literal is used in a context where a primitive char or the wrapper type Character is expected, the compiler will treat the literal as such a value or instance.

val char c = 'c'

Number Literals

Xtend supports roughly the same number literals as Java with a few differences. First, there are no signed number literals. If you put a minus operator in front of a number literal it is treated as a unary operator with one argument (the positive number literal). Second, as in Java 7, you can separate digits using _ for better readability of large numbers. An integer literal creates an int, a long (suffix L) or a BigInteger (suffix BI). There are no octal numbers

42

1_234_567_890

0xbeef // hexadecimal

077 // decimal 77 (*NOT* octal)

-1 // an expression consisting of the unary - operator and an integer literal

42L

0xbeef#L // hexadecimal, mind the '#'

0xbeef_beef_beef_beef_beef#BI // BigInteger

A floating-point literal creates a double (suffix D or none), a float (suffix F) or a BigDecimal (suffix BD). If you use a . you have to specify both, the integral and the fractional part of the mantissa. There are only decimal floating-point literals.

42d // double

0.42e2 // implicit double

0.42e2f // float

4.2f // float

0.123_456_789_123_456_789_123_456_789e2000bd // BigDecimal

Boolean Literals

There are two boolean literals, true and false which correspond to their Java counterpart of type boolean.

Null Literal

The null pointer literal null has exactly the same semantics as in Java.

Type Literals

The syntax for type literals is generally the plain name of the type, e.g. the snippet String is equivalent to the Java code String.class. Nested types use the delimiter '.'.

To disambiguate the expression, type literals may also be specified using the keyword typeof.

Map.Entryis equivalent toMap.Entry.classtypeof(StringBuilder)yieldsStringBuilder.class

Consequently it is possible to access the members of a type reflectively by using its plain name String.getDeclaredFields.

The keyword typeof is mandatory for references to array types, e.g. typeof(int[]

Previous versions of Xtend (2.4.1 and before) used the dollar as the delimiter character for nested types and enforced the use of typeof for all type literals:

typeof(Map$Entry)yieldsMap.Entry.class

Collection Literals

The methods in CollectionLiterals are automatically imported so it’s very easy and convenient to create instances of the various collection types the JDK offers.

val myList = newArrayList('Hello', 'World')

val myMap = newLinkedHashMap('a' -> 1, 'b' -> 2)

In addition xtend supports collection literals to create immutable collections and arrays, depending on the target type. An immutable list can be created like this:

val myList = #['Hello','World']

If the target type is an array as in the following example an array is created instead without any conversion:

val String[] myArray = #['Hello','World']

An immutable set can be created using curly braces instead of the squared brackets:

val mySet = #{'Hello','World'}

An immutable map is created like this:

val myMap = #{'a' -> 1 ,'b' ->2}

Arrays

Java arrays can be created either using a literal as described in the previous section, or if it should be a new array with a fixed size, one of the methods from ArrayLiterals can be used. The generic newArrayOfSize(int) method works for all reference types, while there is a specific factory method for each primitive type.

Example:

val String[] myArray = newArrayOfSize(400)

val int[] intArray = newIntArrayOfSize(400)

Retrieving and setting values of arrays is done through the extension methods get(int) and set(int, T) which are specifically overloaded for arrays and are translated directly to the equivalent native Java code myArray[int].

Also length is available as an extension method and is directly translated to Java’s equivalent myArray.length.

Furthermore arrays are automatically converted to lists (java.util.List) when needed. This works similar to how boxing and unboxing between primitives and their respective wrapper types work.

Example:

val int[] myArray = #[1,2,3]

val List<Integer> myList = myArray

Type Casts

A type cast behaves exactly like casts in Java, but has a slightly more readable syntax. Type casts bind stronger than any other operator but weaker than feature calls.

The conformance rules for casts are defined in the Java Language Specification. Here are some examples:

something as MyClass

42 as Integer

Instead of a plain type cast it’s also possible to use a switch with a type guard which performs both the casting and the instance-of check. Dispatch methods are another alternative to casts that offers the potential to enhance the number of expected and handled types in subclasses.

Infix Operators and Operator Overloading

There are a couple of common predefined infix operators. These operators are not limited to operations on certain types. Instead an operator-to-method mapping allows to redefine the operators for any type just by implementing the corresponding method signature. As an example, the runtime library contains a class BigDecimalExtensions that defines operators for BigDecimals. The following code is therefore perfectly valid:

val x = 2.71BD

val y = 3.14BD

val sum = x + y // calls BigDecimalExtension.operator_plus(x,y)

This is the complete list of all available operators and their corresponding method signatures:

e1 += e2 |

e1.operator_add(e2) |

e1 -= e2 |

e1.operator_remove(e2) |

e1 || e2 |

e1.operator_or(e2) |

e1 && e2 |

e1.operator_and(e2) |

e1 == e2 |

e1.operator_equals(e2) |

e1 != e2 |

e1.operator_notEquals(e2) |

e1 === e2 |

e1.operator_tripleEquals(e2) |

e1 !== e2 |

e1.operator_tripleNotEquals(e2) |

e1 < e2 |

e1.operator_lessThan(e2) |

e1 > e2 |

e1.operator_greaterThan(e2) |

e1 <= e2 |

e1.operator_lessEqualsThan(e2) |

e1 >= e2 |

e1.operator_greaterEqualsThan(e2) |

e1 -> e2 |

e1.operator_mappedTo(e2) |

e1 .. e2 |

e1.operator_upTo(e2) |

e1 >.. e2 |

e1.operator_greaterThanDoubleDot(e2) |

e1 ..< e2 |

e1.operator_doubleDotLessThan(e2) |

e1 => e2 |

e1.operator_doubleArrow(e2) |

e1 << e2 |

e1.operator_doubleLessThan(e2) |

e1 >> e2 |

e1.operator_doubleGreaterThan(e2) |

e1 <<< e2 |

e1.operator_tripleLessThan(e2) |

e1 >>> e2 |

e1.operator_tripleGreaterThan(e2) |

e1 <> e2 |

e1.operator_diamond(e2) |

e1 ?: e2 |

e1.operator_elvis(e2) |

e1 <=> e2 |

e1.operator_spaceship(e2) |

e1 + e2 |

e1.operator_plus(e2) |

e1 - e2 |

e1.operator_minus(e2) |

e1 * e2 |

e1.operator_multiply(e2) |

e1 / e2 |

e1.operator_divide(e2) |

e1 % e2 |

e1.operator_modulo(e2) |

e1 ** e2 |

e1.operator_power(e2) |

! e1 |

e1.operator_not() |

- e1 |

e1.operator_minus() |

+ e1 |

e1.operator_plus() |

The table above also defines the operator precedence in ascending order. The blank lines separate precedence levels. The assignment operators += and -= are right-to-left associative in the same way as the plain assignment operator = is. That is a = b = c is executed as a = (b = c), all other operators are left-to-right associative. Parentheses can be used to adjust the default precedence and associativity.

Short-Circuit Boolean Operators

If the operators ||, &&, and ?: are bound to the library methods BooleanExtensions.operator_and(boolean l, boolean r), BooleanExtensions.operator_or(boolean l, boolean r) resp. <T> T operator_elvis(T first, T second) the operation is inlined and evaluated in short circuit mode. That means that the right hand operand might not be evaluated at all in the following cases:

- in the case of

||the operand on the right hand side is not evaluated if the left operand evaluates totrue. - in the case of

&&the operand on the right hand side is not evaluated if the left operand evaluates tofalse. - in the case of

?:the operand on the right hand side is not evaluated if the left operand evaluates to anything butnull.

Still you can overload these operators for your types or even override it for booleans, in which case both operands are always evaluated and the defined method is invoked, i.e. no short-circuit execution is happening.

Postfix Operators

The two postfix operators ++ and -- use the following method mapping:

e1++ |

e1.operator_plusPlus() |

e1-- |

e1.operator_minusMinus() |

Defined Operators in The Library

Xtend offers operators for common types from the JDK.

Equality Operators

In Xtend the equals operators (==,!=) are bound to Object.equals. So you can write:

if (name == 'Homer')

println('Hi Homer')

Java’s identity equals semantic is mapped to the tripple-equals operators === and !== in Xtend.

if (someObject === anotherObject)

println('same objects')

Comparison Operators

In Xtend the usual comparison operators (>,<,>=, and <=) work as expected on the primitive numbers:

if (42 > myNumber) {

...

}

In addition these operators are overloaded for all instances of java.lang.Comparable. So you can also write

if (startTime < arrivalTime)

println("You are too late!")

Arithmetic Operators

The arithmetic operators (+,-,*,/,%, and **) are not only available for the primitive types, but also for other reasonable types such as BigDecimal and BigInteger.

val x = 2.71BD

val y = 3.14BD

val sum = x + y // calls BigDecimalExtension.operator_plus(x,y)

Elvis Operator

In addition to null-safe feature calls Xtend supports the elvis operator known from Groovy.

val salutation = person.firstName ?: 'Sir/Madam'

The right hand side of the expression is only evaluated if the left side was null.

With Operator

The with operator is very handy when you want to initialize objects or when you want to use a particular instance a couple of time in subsequent lines of code. It simply passes the left hand side argument to the lambda on the right hand and returns the left hand after that.

Here’s an example:

val person = new Person => [

firstName = 'Homer'

lastName = 'Simpson'

address = new Address => [

street = '742 Evergreen Terrace'

city = 'SpringField'

]

]

Range Operators

There are three different range operators. The most useful ones are ..< and >.. which create exclusive ranges.

// iterate the list forwards

for (i : 0 ..< list.size) {

val element = list.get(i)

...

}

// or backwards

for (i : list.size >.. 0) {

val element = list.get(i)

...

}

In addition there is the inclusive range, which is nice if you know both ends well. In the movies example the range is used to check whether a movie was made in a certain decade:

movies.filter[1980..1989.contains(year)]

Please keep in mind that there are other means to iterator lists, too. For example, you may want to use the forEach extension

list.forEach[ element, index |

.. // if you need access to the current index

]

list.reverseView.forEach[

.. // if you just need the element it in reverse order

]

Pair Operator

Sometimes you want to use a pair of two elements locally without introducing a new structure. In Xtend you can use the ->-operator which returns an instance of Pair<A,B>:

val nameAndAge = 'Homer' -> 42

If you want to surface a such a pair of values on the interface of a method or field, it’s generally a better idea to use a data class with a well defined name, instead:

@Data class NameAndAge {

String name

int age

}

Assignments

Local variables can be assigned using the = operator.

var greeting = 'Hello'

if (isInformal)

greeting = 'Hi'

Of course, also non-final fields can be set using an assignment:

myObj.myField = 'foo'

Setting Properties

The lack of properties in Java leads to a lot of syntactic noise when working with data objects. As Xtend is designed to integrate with existing Java APIs it respects the Java Beans convention, hence you can call a setter using an assignment:

myObj.myProperty = 'foo' // calls myObj.setMyProperty("foo")

The setter is only used if the field is not accessible from the given context. That is why the @Property annotation would rename the local field to _myProperty.

The return type of an assignment is the type of the right hand side, in case it is a simple assignment. If it is translated to a setter method it yields whatever the setter method returns.

Assignment Operators

Compound assignment operators can be used as a shorthand for the assignment of a binary expression.

var BigDecimal bd = 45bd

bd += 12bd // equivalent to bd = bd + 12bd

bd -= 12bd // equivalent to bd = bd - 12bd

bd /= 12bd // equivalent to bd = bd / 12bd

bd *= 12bd // equivalent to bd = bd * 12bd

Compound assignments work automatically when the infix operator is declared. The following compound assignment operators are supported:

e1 += e2 |

+ |

e1 -= e2 |

- |

e1 *= e2 |

* |

e1 /= e2 |

/ |

e1 %= e2 |

% |

Blocks

The block expression allows to have imperative code sequences. It consists of a sequence of expressions. The value of the last expression in the block is the value of the complete block. The type of a block is also the type of the last expression. Empty blocks return null and have the type Object. Variable declarations are only allowed within blocks and cannot be used as a block’s last expression.

A block expression is surrounded by curly braces. The expressions in a block can be terminated by an optional semicolon.

Here are two examples:

{

doSideEffect("foo")

result

}

{

var x = greeting;

if (x.equals("Hello ")) {

x + "World!"

} else {

x

}

}

Variable Declarations

Variable declarations are only allowed within blocks. They are visible from any subsequent expressions in the block.

A variable declaration starting with the keyword val denotes a value, which is essentially a final, unsettable variable. The variable needs to be declared with the keyword var, which stands for ‘variable’ if it should be allowed to reassign its value.

A typical example for using var is a counter in a loop:

{

val max = 100

var i = 0

while (i < max) {

println("Hi there!")

i = i + 1

}

}

Shadowing variables from outer scopes is not allowed, the only exception is the implicit variableit.

Variables declared outside of a lambda expression using the var keyword are not accessible from within the lambda expressions.

A local variable can be marked with the extension keyword to make its methods available as extensions (see extension provider).

Typing

The type of the variable itself can either be explicitly declared or it can be inferred from the initializer expression. Here is an example for an explicitly declared type:

var List<String> strings = new ArrayList

In such cases, the type of the right hand expression must conform to the type of the expression on the left side.

Alternatively the type can be inferred from the initializater:

var strings = new ArrayList<String> // -> msg is of type ArrayList<String>

Field Access and Method Invocations

A simple name can refer to a local field, variable or parameter. In addition it can point to a method with zero arguments, since empty parentheses are optional.

Property Access

If there is no field with the given name and also no method with the name and zero parameters accessible, a simple name binds to a corresponding Java-Bean getter method if available:

myObj.myProperty // myObj.getMyProperty() (.. in case myObj.myProperty is not visible.)

Implicit Variables this and it

Like in Java the current instance of the class is bound to this. This allows for either qualified field access or method invocations like in:

this.myField

or it is possible to omit the receiver:

myField

You can use the variable name it to get the same behavior for any variable or parameter:

val it = new Person

name = 'Horst' // translates to 'it.setName("Horst");'

Another speciality of the variable it is that it is allowed to be shadowed. This is especially useful when used together with lambda expressions.

As this is bound to the surrounding object in Java, it can be used in finer-grained constructs such as lambda expressions. That is why it.myProperty has higher precedence than this.myProperty.

Static Access

For accessing a static field or method you can use the recommended Java syntax or the more explicit double colon ::. That means, the following epxressions are pairwise equivalent:

MyClass.myField

MyClass::myField

com.acme.MyClass.myMethod('foo')

com.acme.MyClass::myMethod('foo')

com::acme::MyClass::myMethod('foo')

Alternatively you could import the method or field using a static import.

Null-Safe Feature Calls

Checking for null references can make code very unreadable. In many situations it is ok for an expression to return null if a receiver was null. Xtend supports the safe navigation operator ?. to make such code better readable.

Instead of writing

if (myRef != null) myRef.doStuff()

one can write

myRef?.doStuff

Arguments that would be passed to the method are only evaluated if the method will be invoked at all.

For primitive types the default value is returned (e.g. 0 for int). This may not be what you want in some cases, so a warning will be raised by default. You can turn that off in the preferences if you wish.

Constructor Calls

Constructor calls have the same syntax as in Java. The only difference is that empty parentheses are optional:

new String() == new String

new ArrayList<BigDecimal>() == new ArrayList<BigDecimal>

If type arguments are omitted, they will be inferred from the current context similar to Java’s diamond operator on generic method and constructor calls.

Lambda Expressions

A lambda expression is basically a piece of code wrapped into an object to pass it around. As a Java developer it is best to think of a lambda expression as an anonymous class with a single method, i.e. like in the following Java code :

// Java Code!

final JTextField textField = new JTextField();

textField.addActionListener(new ActionListener() {

@Override

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent e) {

textField.setText("Something happened!");

}

});

This kind of anonymous classes can be found everywhere in Java code and have always been the poor-man’s replacement for lambda expressions in Java. This has been improved with Java 8 lambda expressions, which are conceptually very similar to Xtend lambda expressions. Depending on the selected target language version, Xtend lambdas are translated differently to Java: Java lambdas are generated for Java 8 (since 2.8), while anonymous classes are generated for lower versions.

The code above can be written in Xtend like this:

val textField = new JTextField

textField.addActionListener([ ActionEvent e |

textField.text = "Something happened!"

])

As you might have guessed, a lambda expression is surrounded by square brackets (inspired from Smalltalk). Similarly to a method, a lambda expression may declare parameters. The lambda above has one parameter called e which is of type ActionEvent. You do not have to specify the type explicitly because it can be inferred from the context:

textField.addActionListener([ e |

textField.text = "The command '" + e.actionCommand + "' happened!"

])

You do not need to specify the argument names. If you leave them out, a single argument is named it. If the lambda has more arguments, the implicit names are $1,$2,...,$n depending on the number of arguments of course. Here’s an example with a single argument named it. In this case actionCommand is equivalent to it.actionCommand.

textField.addActionListener([

textField.text = "The command '" + actionCommand + "' happened!"

])

A lambda expression with zero arguments can be written with or without the bar. They are both the same.

val Runnable aBar = [|

println("Hello I'm executed!")

]

val Runnable noBar = [

println("Hello I'm executed!")

]

When a method call’s last parameter is a lambda it can be passed right after the parameter list. For instance if you want to sort some strings by their length, you could write :

Collections.sort(someStrings) [ a, b |

a.length - b.length

]

which is just the same as writing

Collections.sort(someStrings, [ a, b |

a.length - b.length

])

Since you can leave out empty parentheses for methods which get a lambda as their only argument, you can reduce the code above further down to:

textField.addActionListener [

textField.text = "Something happened!"

]

A lambda expression also captures the current scope. Any final local variables and all parameters that are visible at construction time can be referred to from within the lambda body. That is exactly what we did with the variable textField above.

The variable this refers to the outer class. The lambda instance itself is available with the identifier self.

val lineReader = new LineReader(r);

val AbstractIterator<String> lineIterator = [|

val result = lineReader.readLine

if (result==null)

self.endOfData

return result

]

Typing

Lambdas are expressions which produce Function objects. The type of a lambda expression generally depends on the target type, as seen in the previous examples. That is, the lambda expression can coerce to any interface or abstract class which has declared only one abstract method. This allows for using lambda expressions in many existing Java APIs in a similar way as Java 8 lambdas can be used.

However, if you write a lambda expression without having any target type expectation, like in the following assignment:

val toUpperCaseFunction = [ String s | s.toUpperCase ] // inferred type is (String)=>String

The type will be one of the inner types found in Functions or Procedures. It is a procedure if the return type is void, otherwise it is a function.

Xtend supports a shorthand syntax for function types. Instead of writing Function1<? super String,? extends String> which is what you will find in the generated Java code, you can simply write (String)=>String.

Example:

val (String)=>String stringToStringFunction = [ toUpperCase ]

// or

val Function1<? super String,? extends String> same = [ toUpperCase ]

// or

val stringToStringFunction2 = [ String s | s.toUpperCase ] // inferred type is (String)=>String

Checked exceptions that are thrown in the body of a lambda expression but not declared in the implemented method of the target type are thrown using the sneaky-throw technique. Of course you can always catch and handle them.

Anonymous Classes

An anonymous class in Xtend has the very same semantics as in Java (see Java Language Specification). Here’s an example:

val tabListener = new ActionBar.TabListener() {

override onTabSelected(ActionBar.Tab tab, FragmentTransaction ft) {

// show the given tab

}

override onTabUnselected(ActionBar.Tab tab, FragmentTransaction ft) {

// hide the given tab

}

override onTabReselected(ActionBar.Tab tab, FragmentTransaction ft) {

// probably ignore this event

}

};

If Expression

An if-expression is used to choose between two different values based on a predicate.

An expression

if (p) e1 else e2

results in either the value e1 or e2 depending on whether the predicate p evaluates to true or false. The else part is optional which is a shorthand for an else branch that returns the default value of the current type, e.g. for reference type this is equivalent to else null. That means

if (foo) x

is a short hand for

if (foo) x else null

The type of an if expression is the common super type of the return types T1 and T2 of the two expression e1 and e2.

While the if expression has the syntax of Java’s if statement it behaves more like Java’s ternary operator (predicate ? thenPart : elsePart), because it is an expression and returns a value. Consequently, you can use if expressions deeply nested within expressions:

val name = if (firstName != null) firstName + ' ' + lastName else lastName

Switch Expression

The switch expression is very different from Java’s switch statement. The use of switch is not limited to certain values but can be used for any object reference. Object.equals(Object) is used to compare the value in the case with the one you are switching over. Given the following example:

switch myString {

case myString.length > 5 : "a long string."

case 'some' : "It's some string."

default : "It's another short string."

}

the main expression myString is evaluated first and then compared to each case sequentially. If the case expression is of type boolean, the case matches if the expression evaluates to true. If it is not of type boolean it is compared to the value of the main expression using Object.equals(Object).

If a case is a match, that is it evaluates to true or the result equals the one we are switching over, the case expression after the colon is evaluated and is the result of the whole switch expression.

The main expression can also be a computed value instead of a field or variable. If you want to reuse that value in the body of the switch expression, you can create a local value for that by using the following notation which is similar to the syntax in for loops.

switch myString : someComputation() {

..

}

Type guards

Instead of or in addition to the case guard you can specify a type guard. The case only matches if the switch value conforms to this type. A case with both a type guard and a predicate only matches if both conditions match. If the switch value is a field, parameter or variable, it is automatically casted to the given type within the predicate and the case body.

def length (Object x) {

switch x {

String case x.length > 0 : x.length // length is defined for String

List<?> : x.size // size is defined for List

default : -1

}

}

Handling multiple types in one case statement can be realized with a multi-type guard expression. By specifying an arbitrary number of types separated by a | multiple types can be processed by a single case statement. Within the case block, the intersection type is available for further processing.

def length (Object x) {

switch x {

List<?> | Set<?> : x.size // size is defined for intersection type Collection

String case x.length > 0: x.length // length is defined for String

default: -1

}

}

Switches with type guards are a safe and much more readable alternative to instance of / casting cascades you might know from Java.

Fall Through

You can have multiple type guards and cases separated with a comma, to have all of them share the same then part.

def isMale(String salutation) {

switch salutation {

case "Mr.",

case "Sir" : true

default : false

}

}

Ternary Expression

Additionally to the if expression you can use the ternary operator as you are used to from Java.

val x = flag?"Hello":"Goodbye"

For Loop

The for loop

for (T1 variable : arrayOrIterable) expression

is used to execute a certain expression for each element of an array or an instance of Iterable. The local variable is final, hence cannot be updated.

The type of a for loop is void. The type of the local variable can be inferred from the iterable or array that is processed.

for (String s : myStrings) {

doSideEffect(s)

}

for (s : myStrings)

doSideEffect(s)

Basic For Loop

The traditional for loop

for (<init-expression> ; <predicate> ; <update-expression>) body-expression

is very similar to the one known from Java, or even C. When executed, it first executes the init-expression, where local variables can be declared. Next the predicate is executed and if it evaluates to true, the body-expression is executed. On any subsequent iterations the update-expressio is executed instead of the init-expression. This happens until the predicate returns false.

The type of a for loop is void.

for (var i = 0 ; i < s.length ; i++) {

println(s.subString(0,i)

}

While Loop

A while loop

while (predicate) expression

is used to execute a certain expression unless the predicate is evaluated to false. The type of a while loop is void.

while (true) {

doSideEffect("foo")

}

while ((i=i+1) < max)

doSideEffect("foo")

Do-While Loop

A do-while loop

do expression while (predicate)

is used to execute a certain expression until the predicate is evaluated to false. The difference to the while loop is that the execution starts by executing the block once before evaluating the predicate for the first time. The type of a do-while loop is void.

do {

doSideEffect("foo");

} while (true)

do doSideEffect("foo") while ((i=i+1)<max)

Return Expression

A method or lambda expression automatically returns the value of its body expression. If it is a block expression this is the value of the last expression in it. However, sometimes you want to return early or make it explicit.

The syntax is just like in Java:

listOfStrings.map [ e |

if (e==null)

return "NULL"

e.toUpperCase

]

Throwing Exceptions

Throwing Throwables up the call stack has the same semantics and syntax as in Java.

{

...

if (myList.isEmpty)

throw new IllegalArgumentException("the list must not be empty")

...

}

Try, Catch, Finally

The try-catch-finally expression is used to handle exceptional situations. Checked exceptions are treated like runtime exceptions and only optionally validated. You can but do not have to catch them as they will be silently thrown (see the section on declared exceptions).

try {

throw new RuntimeException()

} catch (NullPointerException e) {

// handle e

} finally {

// do stuff

}

For try-catch it is again beneficial that it is an expression, because you can write code like the following and do not have to rely on non-final variables:

val name = try {

readFromFile

} catch (IOException e) {

"unknown"

}

Handling multiple exceptions in a single catch block can be realized using a multi-catch clause. The multi-catch clause can handle an arbitrary number of exceptions separated by |. Within the catch block, the intersection exception type of the exceptions caught by the multi-catch clause is available for further processing. If handling one exception covers another exception handled in the multi-catch clause an error is raised.

def readFile (String path) {

try {

readFromPath (path)

} catch (FileNotFoundException | StreamCorruptedException it) {

logException

}

}

Try With Resources

Like in Java you can use the try-with-resources expression to automatically close resources.

try (val resource = new StringReader("This \n is a text!"))

return resource.read

Synchronized

The synchonized expression does the same as it does in Java (see Java Language Specification). The only difference is that in Xtend it is an expression and can therefore be used at more places.

synchronized(lock) {

println("Hello")

}

val name = synchronized(lock) {

doStuff()

}

Template Expressions

Templates allow for readable string concatenation. Templates are surrounded by triple single quotes ('''). A template expression can span multiple lines and expressions can be nested which are evaluated and their toString() representation is automatically inserted at that position.

The terminals for interpolated expression are so called guillemets «expression». They read nicely and are not often used in text so you seldom need to escape them. These escaping conflicts are the reason why template languages often use longer character sequences like e.g. <%= expression %> in JSP, for the price of worse readability. The downside with the guillemets in Xtend is that you will have to have a consistent encoding. Always use UTF-8 and you are good.

If you use the Eclipse plug-in the guillemets will be inserted on content assist within a template. They are additionally bound to CTRL + < and CTRL + > for « and » respectively.

Let us have a look at an example of how a typical method with a template expressions looks like:

def someHTML(String content) '''

<html>

<body>

«content»

</body>

</html>

'''

As you can see, template expressions can be used as the body of a method. If an interpolation expression evaluates to null an empty string is added.

Template expressions can occur everywhere. Here is an example showing it in conjunction with the powerful switch expression:

def toText(Node n) {

switch n {

Contents : n.text

A : '''<a href="«n.href»">«n.applyContents»</a>'''

default : '''

<«n.tagName»>

«n.applyContents»

</«n.tagName»>

'''

}

}

Comments in Templates

Normal single line comments //... and multiline comments /* ... */ will not work inside a template expression. However, you can comment out a complete line inside a template expression using ««« ......

def someHTML(String body) '''

<html>

<body>

««« this will not be visible in the result

««« nor will this: «body»

</body>

</html>

'''

For convenience you can use the normal toggle comment commands from context menu or via shortcuts

- On PC

- CTRL + 7

- CTRL + /

- CTRL + ⇧ + C

- On Mac

- ⌘ + 7

- ⌘ + /

- ⌘ + ⇧ + C

Conditions in Templates

There is a special IF to be used within templates:

def someHTML(Paragraph p) '''

<html>

<body>

«IF p.headLine != null»

<h1>«p.headline»</h1>

«ENDIF»

<p>

«p.text»

</p>

</body>

</html>

'''

You can also use IF...ELSE...ENDIF or IF...ELSEIF...ENDIF expressions:

def someHTML(Paragraph p) '''

<html>

<body>

«IF p.headLine != null»

<h1>«p.headline»</h1>

«ELSE»

<h1>«p.standartHeadline»</h1>

«ENDIF»

<p>

«p.text»

</p>

</body>

</html>

'''

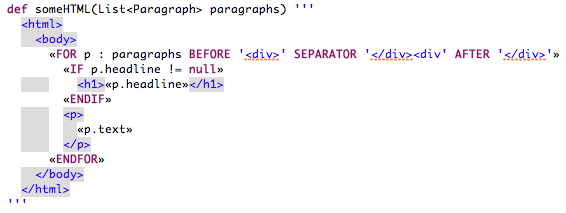

Loops in Templates

Also a FOR expression is available:

def someHTML(List<Paragraph> paragraphs) '''

<html>

<body>

«FOR p : paragraphs»

«IF p.headLine != null»

<h1>«p.headline»</h1>

«ENDIF»

<p>

«p.text»

</p>

«ENDFOR»

</body>

</html>

'''

The for expression optionally allows to specify what to prepend (BEFORE), put in-between (SEPARATOR), and what to put at the end (AFTER) of all iterations. BEFORE and AFTER are only executed if there is at least one iteration. (SEPARATOR) is only added between iterations. It is executed if there are at least two iterations.

Here is an example:

def someHTML(List<Paragraph> paragraphs) '''

<html>

<body>

«FOR p : paragraphs BEFORE '<div>' SEPARATOR '</div><div>' AFTER '</div>'»

«IF p.headLine != null»

<h1>«p.headline»</h1>

«ENDIF»

<p>

«p.text»

</p>

«ENDFOR»

</body>

</html>

'''

Typing

The template expression is of type CharSequence. It is automatically converted to String if that is the expected target type.

White Space Handling

One of the key features of templates is the smart handling of white space in the template output. The white space is not written into the output data structure as is but preprocessed. This allows for readable templates as well as nicely formatted output. The following three rules are applied when the template is evaluated:

- Indentation in the template that is relative to a control structure will not be propagated to the output string. A control structure is a

FOR-loop or a condition (IF) as well as the opening and closing marks of the template string itself. The indentation is considered to be relative to such a control structure if the previous line ends with a control structure followed by optional white space. The amount of indentation white space is not taken into account but the delta to the other lines. - Lines that do not contain any static text which is not white space but do contain control structures or invocations of other templates which evaluate to an empty string, will not appear in the output.

- Any newlines in appended strings (no matter they are created with template expressions or not) will be prepended with the current indentation when inserted.

Although this algorithm sounds a bit complicated at first it behaves very intuitively. In addition the syntax coloring in Eclipse communicates this behavior.

The behavior is best described with a set of examples. The following table assumes a data structure of nested nodes.

class Template {

def print(Node n) '''

node «n.name» {}

'''

}

node NodeName {}

The indentation before node «n.name» will be skipped as it is relative to the opening mark of the template string and thereby not considered to be relevant for the output but only for the readability of the template itself.

class Template {

def print(Node n) '''

node «n.name» {

«IF hasChildren»

«n.children.map[print]»

«ENDIF»

}

'''

}

node Parent{

node FirstChild {

}

node SecondChild {

node Leaf {

}

}

}

As in the previous example, there is no indentation on the root level for the same reason. The first nesting level has only one indentation level in the output. This is derived from the indentation of the IF hasChildren condition in the template which is nested in the node. The additional nesting of the recursive invocation children.map[print] is not visible in the output as it is relative the surrounding control structure. The line with IF and ENDIF contain only control structures thus they are skipped in the output. Note the additional indentation of the node Leaf which happens due to the first rule: Indentation is propagated to called templates.